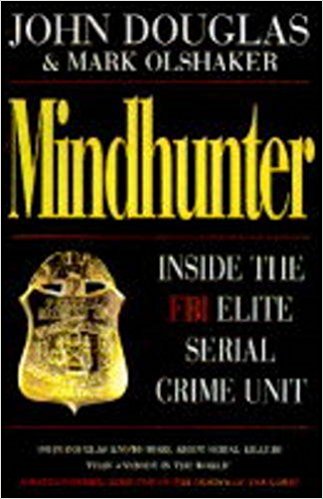

Book Review: John Douglas and Mark Olshaker, Mindhunter (Arrow Books: London 1997)

I finished ‘reading’ Mindhunter on the train from Euroa to Melbourne the other night. I say ‘reading’ with caution. It’s not a great read, thanks to Douglas’ monotone prose style. It’s better treated as a catalogue of the more interesting serial murders of the late twentieth-century.

You can largely skip most of the discussion of criminal profiling, given that the entire discipline seems to be based on some very wobbly science. It’s also probably best to try and ignore the authorial voice as much as you can, since Mr Douglas largely impresses as an insufferable know-it-all. At one stage he imagines himself as a Lone Ranger, riding into town to dispense justice beyond the capacity of the knuckle-draggers in the local police force (an attitude which must have made the FBI popular among law enforcement) [pp.279 and 361]. In one of the closing chapters he over-reaches when he describes himself furiously telling a psychiatrist how the latter ought to be conducting assessments. The tale ends with him saying: “He [the psychiatrist] didn’t have an answer” [p.336]. Actually, he was probably too polite to say it: that he was significantly better qualified to assess criminals than the combination of cop and snake-oil salesman who was his interlocutor.

Shorn of its faults, then, this 375-page book would condense to a neat 40 pages or so giving the basics of some interesting true crime. My recommendation? Skim it in an afternoon and then look up the more interesting bits on Wikipedia. Wikipedia’s editorial standards are higher.